The United Nations’ scientific panel on climate change issued a report that basically says the end of the world could happen in 22 years. The Doomsday Clock, that symbol devised to represent the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe, is set at two minutes to midnight, the closest it has been since 1953. Nope, we’re not describing the latest friggin’ Mad Max, these are today’s real-world news. All around us, it seems like dystopias are in fashion, and not necessarily because it’s très chic.

By Benjamin Pineros

Many dystopias no longer feel like visions of a future far away. High-tech surveillance states, artificial intelligence interfering in elections and lab-grown steaks are all things that have jumped from the pages of speculative fiction to our real world. If we think about it, we’re practically living in a dystopia that could have very well come out of the mind of someone like William Gibson or George Orwell.

The first precursors of dystopian fiction appeared in late 19th-century literature, and over the last hundred years or so the genre has spread out to almost every other art form. Comics, in particular, has proved to be a fertile medium to develop these cautionary tales of society gone wrong.

We’ve decided to showcase five of the most fascinating dystopian tales ever told in comic book form, stories of disgusting organic cities, virtual sex, fallen superheroes, and desperate societies plunging into anarchy. These dark visions serve both as exquisite examinations of what it means to be human, and resounding presages of the bleak place we could end up at if we keep ignoring the warnings.

So have your Prozac ready, play Shiny Happy People on repeat, and prepare yourself to take your existential angst for a hell of a ride. Weltschmerz guaranteed.

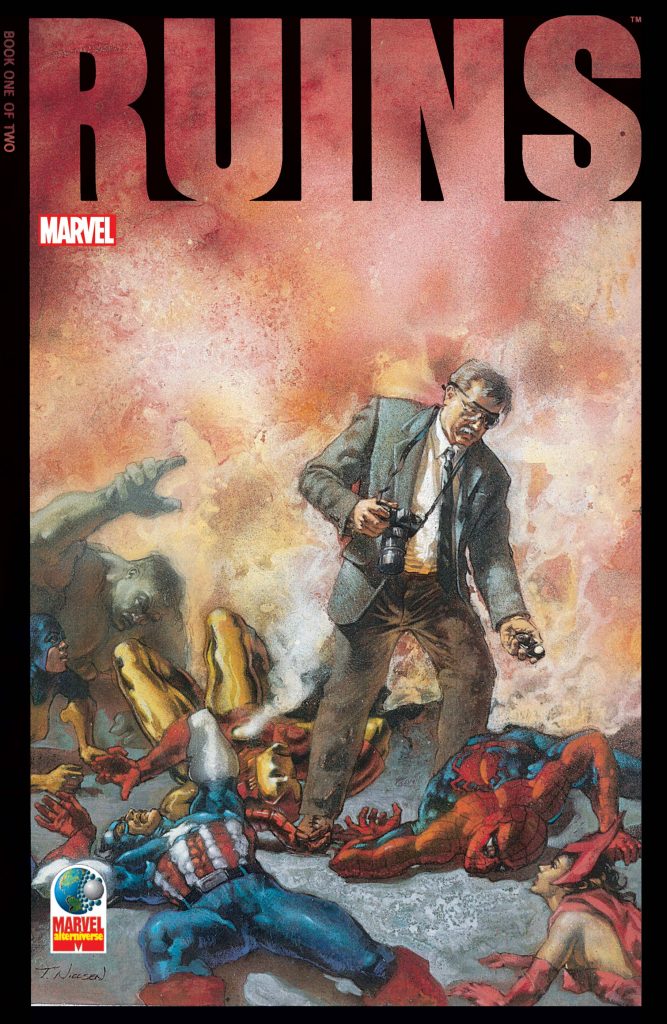

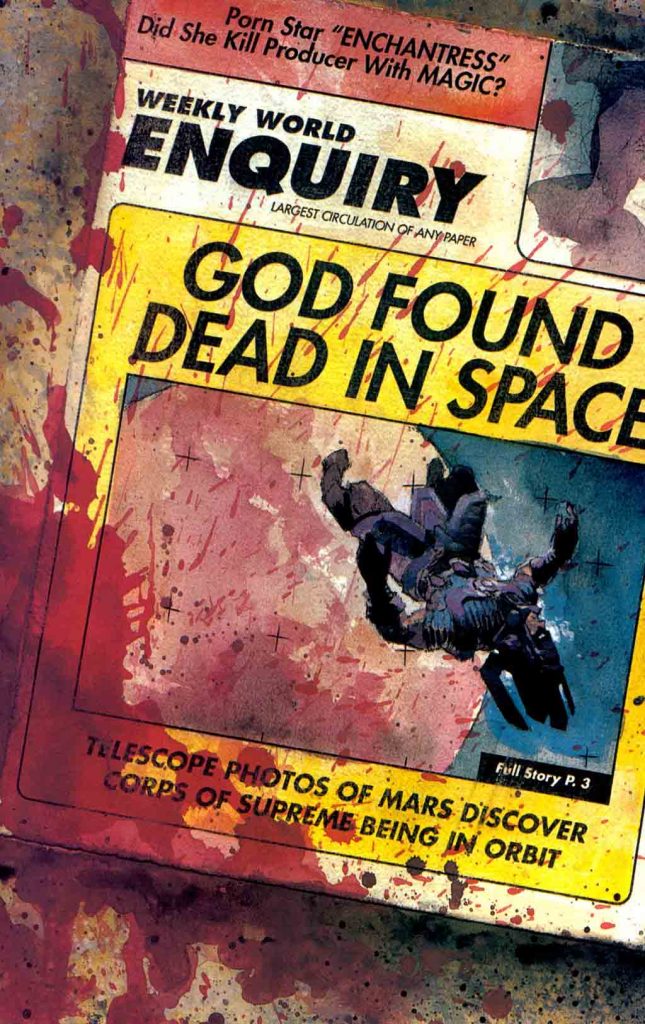

Ruins (Marvel Comics, 1995)

“You ever get the feeling it’s all gone wrong Sheldon? Like, maybe all this weird, sick stuff that happens should really be somethin’ wonderful?”

That line of dialogue by Nick Fury from the first issue of Ruins pretty much describes the whole premise of this astonishing, depressing, and thought-provoking mini-series from the 90s.

This title needs a bit of backstory so bear with me…

For hardcore comic book fanatics, Marvels is something of a sacred book. The four-issue miniseries from 1994 by Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross was developed as the ultimate love letter to the company’s long history. In a very realistic tone, and told from the perspective of a photo reporter called Phil Sheldon, the story follows the progressive apparition of superheroes, villains and mutants in our world and documents society’s reaction to these amazing beings.

Sheldon is witness to some of the most iconic events throughout Marvel’s publishing history, from the original Human Torch’s appearance in 1939 to Gwen Stacy’s death in the 70s. The book, like its title suggests, is a celebration of these wonders, an exaltation of super-powered beings as another element of everyday life, bringers of both chaos and hope.

Ruins, on the other hand, is a completely different ride.

This two-issue mini-series published in 1995 just one year after Marvels is a tale of wonder gone horribly wrong. What if the introduction of these fantastical beings just brought forward humanity’s worst instincts?

Written by Warren Ellis, with gorgeous painted art by Terese Nielsen, her husband Cliff Nielsen, and Chris Moeller, in this tale, photo reporter Phil Sheldon is not witness to the rise of these outstanding beings, but an attestant to their miserable demise.

It spins Marvels on its head and instead of honoring the naivete of the Silver Age of comics, it plunges superheroes into a cesspool of cynicism, misery and hopelessness.

Jean Grey (a.k.a. Dark Phoenix from the X-Men) is a desperate prostitute, the Avengers are a cell of anti-government revolutionaries and Bruce Banner contracted a hideous form of cancer from his exposure to gamma rays instead of the superpowers of The Hulk.

Set in the late 60s in the midst of the Vietnam war and the Civil Rights Movement, Ellis and co. rewrite the Marvel Universe as this bleak world of hunger, poverty and sickness. It’s a shocking experience to see all these heroes that popular culture has idolized for more than half a century, turned into weak, vulnerable, wretched poor souls at mercy of such puerile things like disease and human nature.

Although extremely bleak, the universe of Ruins is incredibly intriguing. If this short mini-series has any problem, it’s that it ends up crumbling under the weight of its own rich worldbuilding. It takes the trouble to create a vast universe only to wrap up the story after just 63 pages.

The title is collected in a trade paperback called “Marvels Companion”. Available at:

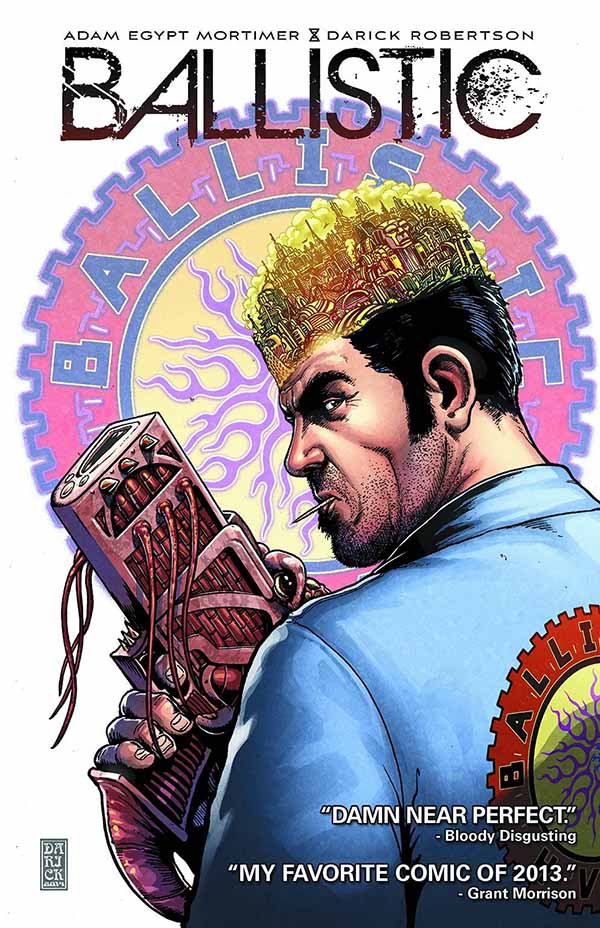

Ballistic (Black Mask Studios, 2013)

Bam! You open the book and the first thing you see is a hyper-detailed closeup of a fucking brutal punch in the face. Now that’s how you start a comic!

Not to be confused with the popular character from Cyberforce, – the superhero team from Image Comics – Ballistic is a tale of crime set in one of the wildest exercises in worldbuilding ever done in comics.

In the early 21st century, the Western world has collapsed because of an unprecedented banking and ecological crisis.

American cities have literally turned into “flowing rivers of shit” and the rest of the world is in flames. Amidst this grim scenario, a billionaire industrialist takes an island of waste located somewhere in the Philippine Sea and reforms it to create Repo City State, a breathing, biotechnological wonder.

Heavily inspired by David Cronenberg’s twisted bio-contraptions, Repo City’s foundation is not concrete, but DNA. In this fantastic dystopia buildings are gown from live tissue and electricity is carried throughout the city using nervous system fibres. Plastic is replaced by hyper-flexible membranes made of spider silk. Bone and skin are used to make computers, clothes and vehicles. Power mainly comes from red algae energy plants and other living structures that suck energy directly from sunlight.

Everything in Repo City looks and feels disgusting, people eat cloned body parts, phones are implanted in one’s skin and information is stored in liquid. If an appliance stops working you need more of a doctor than a technician to fix it.

Surprisingly, every element behind the conception of this insane metropolis has an origin in a real-life scientific advancement, which makes Ballistic even more mind-blowing.

In this genetically designed city, order is instituted by a curious alliance between corporations and crime bosses who are given free rein to exert law in their sector. Culture in Repo is an inventive smashup of Asian tradition with western pop, with vibrant, frenetic streets in which you can hear chatter in Korean, English and Singlish: an English-based creole language spoken in Singapore.

Butch is the everyman in this tale, an air conditioner repairman with serious criminal aspirations. His best friend is a genetically-engineered sentient gun with a loud mouth and a bad attitude, a literal brother-in-arms.

This five-issue mini-series written by Adam Egypt Mortimer and drawn by superstar Darick Robertson follows Butch in his quest to pull off the ultimate heist, that one job that will save him from the dullness of his nine to five work and earn him the respect of the criminal underground.

But of course, like in all tales of amateur crime, things go horribly wrong.

Ballistic is so impressive, Grant Morrison, one of the most lauded authors of the comic industry in the last four decades, named it as his favorite comic of 2013.

If you like ingenious stories of sex and crime, where guns get high, air conditioners get sick, and TV’s can hallucinate, look no further.

The title is collected in one trade paperback.

Amazon.com | Booksetc.co.uk | Bol.com

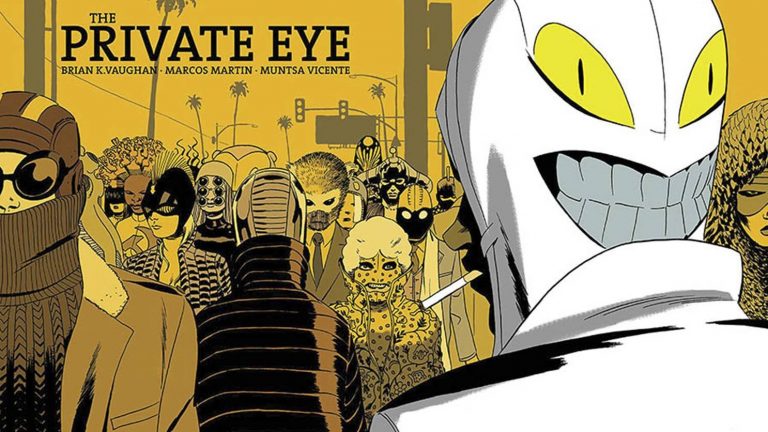

The Private Eye (Panel Syndicate, 2013)

In the early 21st century, a series of security failures led to a spectacular burst of the cloud, where the personal information behind every comment, post and search ever made was disclosed to the general public.

This massive privacy breach led to the total dismantlement of society, forcing a new era in which personal identity is every citizen’s most precious asset.

Just imagine if every search you’ve ever done was put into the spotlight along with all your personal information. What would happen if your grandmother, mother-in-law and boss had access to all of your naughty midnight Googling?

Welcome to Los Angeles in 2076, the frightening and utterly engrossing world of The Private Eye.

This vision of the future, part Orwell’s 1984, part The Truman Show, is set decades after the digital cloudburst. With the internet banned and dismantled, TV and books become people’s most popular distractions. Citizens wear elaborate masks and use aliases to protect their identity, and the press has morphed into a weird entity that fusions the duty to inform with the authority to police.

In this world, paparazzi are illegal, and their job isn’t to follow the shenanigans of the rich and famous. They act more like private detectives, hired to find a person’s true name.

The ten-issue limited series, written by Brian K. Vaughan, with art by Marcos Martin and Muntsa Vicente, follows the story of an unlicensed paparazzi immersed by chance in a case that’s too big for his expertise.

It was more than fitting that a story about digital privacy was the first to inaugurate the initiative called “Panel Syndicate”, a collective of high profile creators that joined forces to innovate the way comics are distributed.

Inspired by Radiohead’s “pay-what-you-want” launch of their album In Rainbows, the comic was published on the Panel Syndicate website in March 2013, with users given the liberty to choose whatever they wanted to pay to read it.

The story plays out as a classic Crime Noir tale with evident nods to the 50s but updated to fit a neon-lit colored aesthetic. Paced like a skilful action-thriller and done in landscape format to fit a computer screen, the art is absolutely flawless in every way.

Dynamic and vibrant, Marcos Martin resorts to detail when it serves a purpose in the story, but isn’t afraid of going the minimalistic route when it’s warranted.

Perfectly constructed to leave the reader with a huge cliffhanger at the end of each issue, The Private Eye is a very intelligent, effective meditation on our current information society.

Is it worth to surrender our personal privacy in the name of security?

Winner of one Eisner Award for Best Digital/Web Comic and a Harvey for Best Online Comics Work in 2015, the comic is currently available for digital download at The Panel Syndicate website or in hardcover format from Image Comics.

Amazon.com | Booksetc.co.uk | Bol.com

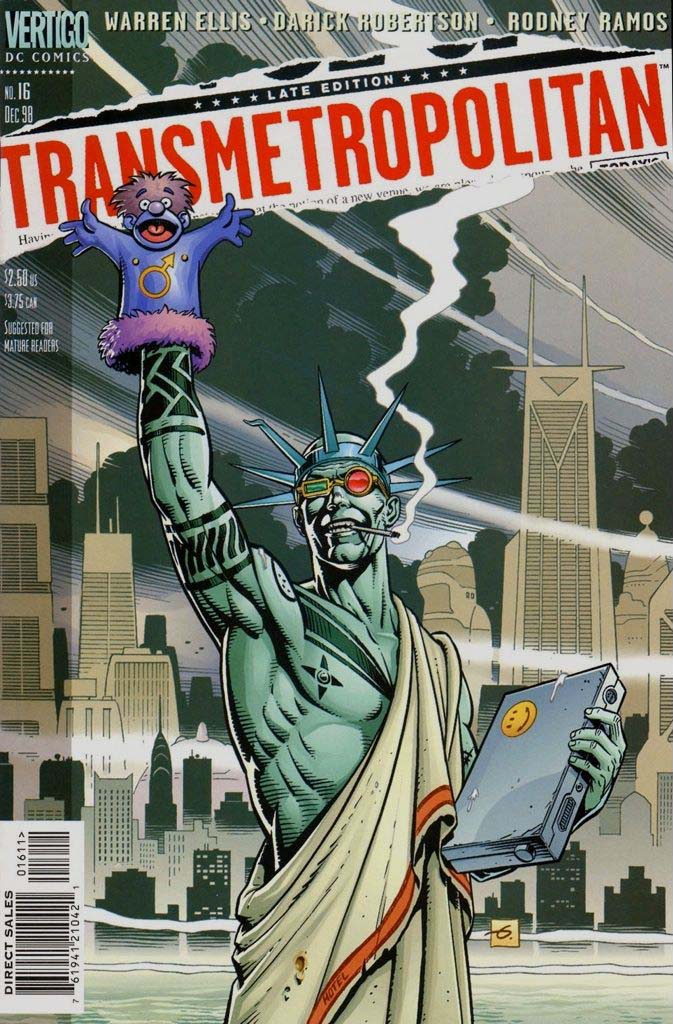

Transmetropolitan (DC Vertigo, 1997)

The US president is an amoral, narcissistic, sex obsessed, overweight bully, who uses his power solely to feed his self-interest. His rise to the top was only possible thanks to a complacent society, numbed by overwhelming consumerism and summed in an excruciating state of apathy.

To make matters even worse, due to unprecedented technological advances, information spreads at real time, creating such an overload of data that it’s almost impossible for the public to discern truth from falsehood.

No, I’m not describing current day politics. This is the world of Transmetropolitan, the frighteningly prescient 60-issue comic book from 1997 written by Warren Ellis with art by the great Darick Robertson.

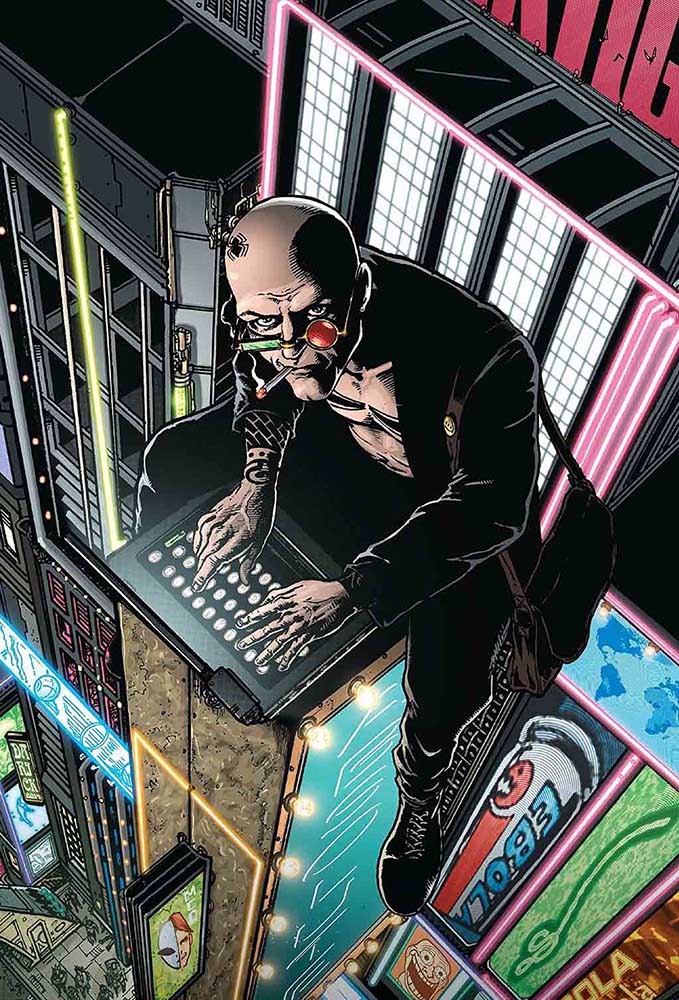

Set in “The City”, a brutal megalopolis in the 23rd century, – a mix of San Francisco, New York and Chicago – the story follows renegade journalist Spider Jerusalem, a bitter, chain-smoking, cynical drug addict who turns out to be America’s only hope.

Heavily based in man-turned-myth Hunter S. Thompson, Jerusalem is probably the most flawed character in the book, even more so than the villains he confronts.

He’s a highly troubled, foulmouthed nonconformist who hates everything and everyone – that includes dogs – and yet, despite all his shortcomings, he embodies the immaculate ideal of a free press that relentlessly pursues the truth in service of the governed, not the governors.

Spider starts out the book as this long-bearded, dishevelled hermit physically reminiscent of comic book writer Alan Moore. He has been living in the mountains in self-exile for five years, having spent all the money of a substantial advance from a publishing contract he hasn’t yet fulfilled.

Our tattoo-ridden protagonist comes back to The City forced not only to complete the books in the contract but to take up work in a newspaper to support his writing.

Throughout the 60-issue run, we are witness to sardonic Jerusalem turning out to be this perverted version of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra; an “enlightened” being descending from his high mountain to bring truth to the wretched, poor devils below.

Spider’s quest pits him against the police, mainstream media, and not one, but two US presidents. This is not a superhero comic book at all, and yet, the general template perfectly fits the bill; Jerusalem has sidekicks, a rogue’s gallery, and yeah, even a set of superpowers: his unflinching approach to the truth and a blunt, persuasive writing style.

Oh, and he’s also good at kicking-ass.

Transmetropolitan is vulgar, nihilistic and blatantly sarcastic, but at its core, it’s a tremendously idealistic manifesto.

We’re living in times when the truth is under assault. Politicians, corporations and individuals concoct their own tailored version of reality and swear by their fabrications, making of the cultural discourse something akin to a screaming contest among deafs.

And right in the middle of all this mess stands the media, still waving the flag of truth, but these days more preoccupied in metrics like page views and engagement time over the actual content.

Transmetropolitan serves as the ultimate homage to a free uncompromised press, a tale of one man that is willing to give his life in the quest for “The Truth”. And such a message during these mad days is not only relevant but necessary. We need more guys like Spider.

The title is collected in two presentations, a premium series of three slipcased, oversized volumes from DC/Vertigo and a series of trade paperbacks labelled 0 to 10.

Amazon.com | Booksetc.co.uk | Bol.com

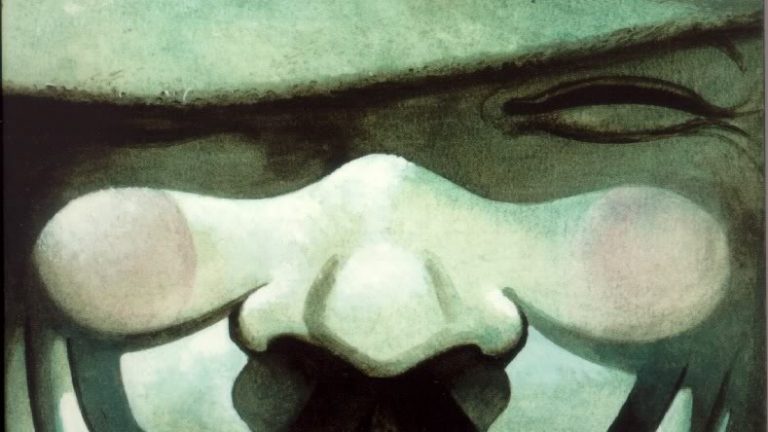

V for Vendetta (Quality Communications/DC Vertigo, 1982)

To include V for Vendetta in a list of dystopias or “best comics” is as necessary as it is redundant. This ten-issue miniseries by Alan Moore and David Lloyd (with additional art by Tony Weare) is not only one of the most celebrated comic books of all time, but it’s probably the only work in the medium that can brag about inspiring political action in real life.

The problem –if it can be considered a problem at all, I mean, it’s not the book’s fault to be hyped to oblivion– with V for Vendetta is that it has become one of those creations like Citizen Kane or the Mona Lisa, that end up overwhelmed by the weight of their own success. All these are pieces of art so influential, they’ve turned into a mandatory cultural cliché.

Notwithstanding, if we isolate the actual comic from all the noise, it’s evident that we stand in front of a genuine, massive artistic achievement. No shit, right? It’s friggin’ Alan Moore we’re talking about here.

The world of V for Vendetta is an elaborate, incredibly rich cultural pastiche with influences that go from Orwell’s 1984 to Vincent Price’s deliciously twisted character from the 1971 comedy horror film The Abominable Dr. Phibes.

Elements from Judge Dredd, David Bowie, Batman, The Shadow and Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and more, all converge to form a singular, pessimistic vision of the future, one that almost 40 years after it’s original release seems frighteningly relevant.

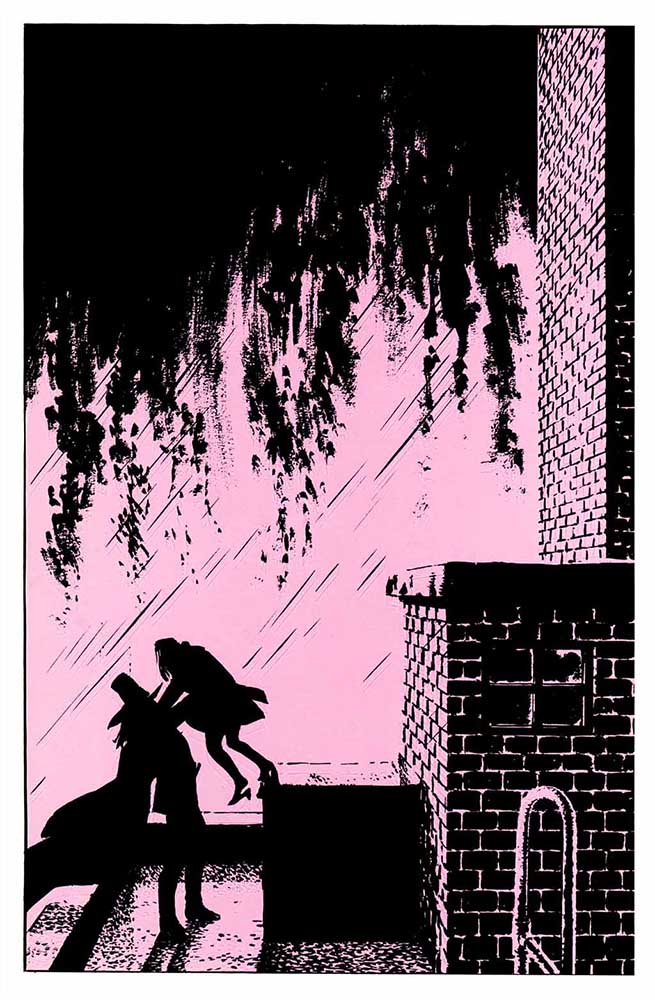

The story’s main premise is the contraposition of the antagonistic ideas of Anarchy and Totalitarianism. “Lives of your own, or a return to chains” as Evey Hammond, one of the main characters says at one point.

Interestingly, the tale starts with these boundaries clearly defined, and as the narrative advances, the lines blur until they become almost indiscernible.

The world has plunged into a profound economic crisis which lead to a devastating global nuclear conflict. Amidst this dark hour, fascist politicians have stepped into the scene offering security and stability, and a desperate, vulnerable society has taken the bait. Sounds familiar?

The world of V for Vendetta is one of governments closing their frontiers and casting nations into international isolation. Politicians unify people around a hand-picked, carefully constructed scapegoat that represents everything that’s going wrong in the country.

Alan Moore takes the conditions that have lead to the rise of authoritarian regimes of different affiliations in the past, –Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the 30s, Thatcherism in the 80s– and transposes it into the near future.

“It’s 1988 now. Margaret Thatcher is entering her third term of office and talking confidently of an unbroken Conservative leadership well into the next century…” Moore wrote in his introduction to the 1988 collected edition of the book. “The government has expressed a desire to eradicate homosexuality, even as an abstract concept and one can only speculate as to which minority will be next legislated against. I’m thinking of taking my family and getting out of this country soon, sometime over the next couple of years. It’s cold and it’s mean-spirited and I don’t like it here anymore. Goodnight England.”

The playbook of fear-mongering and polarization is trending again today, as leaders like Bolsonaro, Trump and Wilders are gaining ground by pouring fire on the collective frustrations of their people.

Initially published in 1982, the most shocking virtue of V for Vendetta is its ability to remind us of events from the past, describe our present, and warn us about the future all at the same time. And now more than ever, it stands as a prescient, cautionary tale of the dark paths we as a society, are still prone to take.

V for Vendetta is available as a graphic novel at: Amazon.com | Booksetc.co.uk | Bol.com

Submarine Channel

Submarine Channel